Fear in the market: Tariffs, Europe re-armament and Fed uncertainty

A recap of what is happening and how it is affecting markets

Growth & tariffs scare

Tariffs have once again taken centre stage, and the market is reacting pre-emptively and aggressively. But this isn’t your typical inflation-driven selloff. It’s something deeper – a psychological reassessment that is prompting widespread risk reduction across various sectors, notably within Technology and Semiconductors. The current market behaviour suggests a reaction not to a tangible deterioration in underlying fundamentals, but rather to the introduction of uncertainty into an already delicate macroeconomic narrative.

The S&P 500 is down 20% from its recent highs and has finished the worst quarter since Q3 2022 (and only the 2nd losing quarter since then). Similarly, the Nasdaq had its worst month since December 2022. On the other hand, we had an historic quarter for European stocks with the pan-European Stoxx 600 outpacing the S&P 500 by nearly 17% in Q1 (when measured in dollar terms) – a record outperformance.

The degrossing has been strong. Last week the hedge funds sold the second-largest amount of global technology stocks in 5 years, according to Goldman Sachs data. This was only smaller than the early August 2024 sell-off. The most activity was seen in U.S. tech which accounted for 75% of the net selling. Not even the early stages of the 2022 bear market experienced such a rapid exit from these stocks. The sector has led this quarter’s losses with the Nasdaq 100 index declining by 13% over the last 6 weeks.

Bond yields have been pushing lower during the past few weeks as investors seek safe-haven assets amid growing concerns over the U.S. economic outlook and the impact of escalating trade tensions. Consequently, Gold is at its historical highs reaching $3’100 per ounce (+19% YTD).

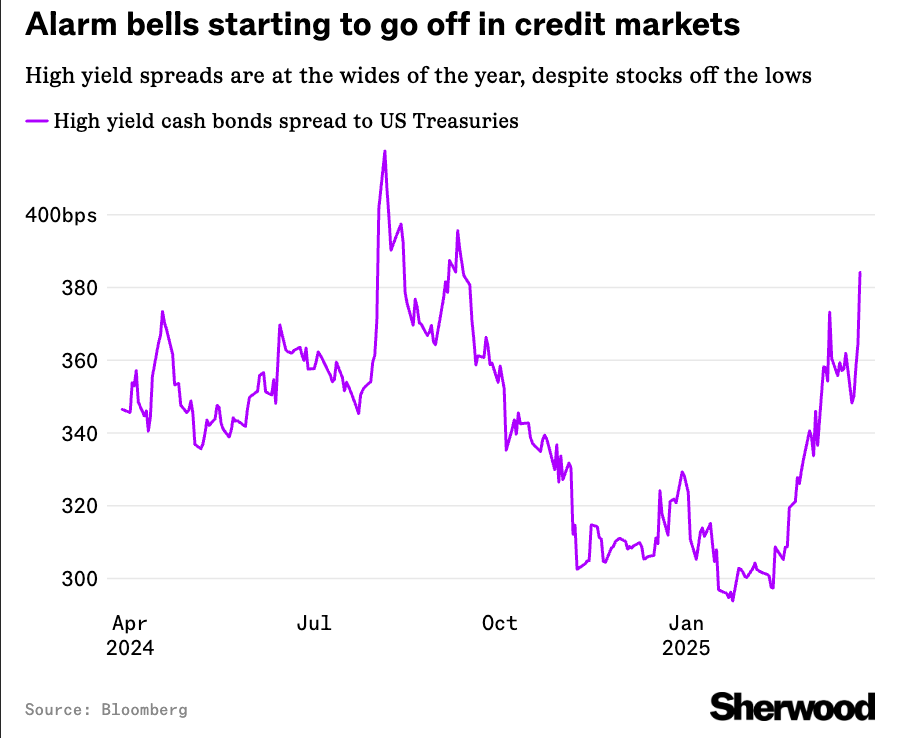

Even more interestingly, credit spreads are at their 2025 high. Additionally, the biggest U.S. High Yield ETF (HYG) is showing extreme stress – with Put options activity at the 99th percentile. While the market has not seen much “crash protection” in equities, we are seeing those dynamics in the biggest high-yield ETF. And when credit markets hedge this aggressively, it’s often a warning shot for equities.

The issue isn’t inflation, it's confidence. The fear around April 2 isn’t based on what has happened – it's based on what might happen if new, unexpected structural policies are introduced. Businesses are already pricing in worst-case scenarios: blanket tariffs, retaliatory trade measures, and even further deterioration in U.S.-China relations. This pervasive fear is impacting every earnings model and forward-looking forecast. Enterprises don’t invest aggressively when they can’t predict their input costs. Consumers don’t spend as freely when headlines suggest their everyday goods are about to get 10-20% more expensive. And markets don’t bottom when the narrative is still deteriorating.

Another noteworthy development is the recent surge in bearish sentiment among consumers regarding stock market expectations. The Conference Board's Consumer Confidence survey revealed the largest two-month jump in consumers expecting lower stock prices in the year ahead, a contrarian signal that could presage market shifts.

In Europe, the economic landscape presents a more mixed picture, in particular after the historical announcement of the huge re-arm plan. France is facing headwinds, while the rest of Europe, including Germany, appears to be on a steadier path. Germany's IFO index has shown positive signs, with both expectations and the current situation exceeding forecasts, bolstered by fiscal spending programs. Yet, the overarching concern for the European economy remains demand. Inflation, on the other hand, presents a more promising outlook, with forecasts suggesting that tariffs will be offset by increased fiscal spending.

As usual, markets work on a forward discounting mechanism and the pain is being priced in before the damage actually occurs – and that’s exactly the kind of setup that historically resolves with an upside reversal once the event passes and doesn’t live up to the hype. So, unless April 2 brings an actual negative structural surprise, we have likely seen the near-term bottom.

U.S. Tariffs: a looming shadow over the markets

One of the most significant factors influencing the global economic outlook is the resurgence of U.S. tariffs. The Trump administration is set to unveil further details of its tariff plans on April 2nd, a date already dubbed “Liberation Day” by some market participants. This looming deadline has injected a significant degree of uncertainty into the markets, with analysts drawing parallels to the market turbulence experienced in 2018.

The exact breadth and scale of the tariffs remain to be seen, and a cycle of tit-for-tat escalation is also possible in the weeks following the announcement, potentially triggering further bouts of market volatility.

Goldman's chief political strategist Alec Phillips says "the risks lean toward an initial tariff announcement that negatively surprises markets". For starters, he notes that while markets have taken comfort from Treas Sec Bessent saying only 15% of countries might face tariffs (the "dirty 15"), those countries represent 87% of all imports.

The anticipation of these tariffs has already led to a rotation in investor sentiment, with a shift from international to domestic stocks. This trend reflects concerns that U.S. companies with high international revenue exposure are particularly vulnerable to the negative impacts of tariffs.

The potential implications of these tariffs are far-reaching. Deutsche Bank analysis suggests that reciprocal tariffs could add anywhere from 4 to 14 percentage points to the overall U.S. tariff rate, relative to the 2024 level of 2.5%. This could result in a significant drag on U.S. real GDP growth, potentially ranging from -25 basis points to as high as negative 120 basis points. Furthermore, core PCE inflation could see an increase of anywhere from a couple of basis points to potentially 1.2%.

The Fed's response to these tariffs remains a key point of uncertainty. While milder tariff outcomes might allow the Fed to maintain its current stance, more aggressive scenarios could trigger a recession. In such a case, the Fed might be compelled to “look through” tariff-driven inflation and prioritize a weakening labour market, provided that inflation expectations remain anchored. This could potentially lead to a situation where the Fed breaks with conventional policy rules.

U.S. recession fears continue to rise

Last week’s economic data were disconcerting, including the slide in consumer confidence, lacklustre consumer spending, and persistently high inflation. The intensifying trade war and DOGE cuts are behind all this and with last week’s announcement of big tariff increases on vehicle imports and the coming reciprocal tariffs, things are expected to get worse. Recession remains less likely than not only because layoffs remain low and job and income growth remain positive.

Unsurprisingly, Goldman Sachs has reportedly raised the probability of a U.S. recession from 20% to 35% and expects higher tariff rates. In a move likely to be followed by other forecasters, economists at Goldman Sachs just gave a stagflationary twist to their U.S. economic forecasts. Goldman has raised its tariff forecast for the 2nd time in a month. The bank states that "higher tariffs are likely to boost consumer prices" and has raised its year-end 2025 core PCE forecast by 0.5% to 3.5% year-over-year. Goldman also cut its Q1 GDP estimate to just 0.2%, and cut its full year 2025 GDP forecast by 0.5% to 1.0% on a Q4/Q4 basis and by 0.4% to 1.5% on an annual average basis. The bank raised its 2025 unemployment rate forecast by 0.3% to 4.5%. Finally, the bank now sees a 12-month recession probability of 35%, up from the previous estimate of 20% reflecting “our lower growth baseline, the sharp recent deterioration in household and business confidence, and statements from White House officials indicating greater willingness to tolerate near-term economic weakness in pursuit of their policies.”

What makes this moment unique is that the selloff isn’t driven by traditional macro deterioration. It’s not about labour markets breaking or inflation surging unexpectedly. Instead, it’s about a policy overhang that introduces forecasting risk – and that is precisely what markets hate the most. The psychological impact is real: CFOs and CEOs are pausing capex decisions, freezing hiring, and lowering guidance not because the business is falling apart, but because the range of possible outcomes is too wide to plan around. For companies selling advertising, cloud services, or enterprise software that uncertainty hits doubly hard. These are businesses priced on forward-looking growth, and when clients delay spending decisions, it shows up as slower bookings, lower utilization, and weaker visibility – even if the long-term story remains intact.

In the meantime, what we are experiencing is a repricing of risk – not just in valuations, but in corporate behaviour. Companies are bracing for a world where policy risk becomes a key variable to consider in taking business decisions. They’re recalibrating their supply chains, reassessing pricing power, and looking for ways to diversify away from tariff exposure. But here’s the twist: many of these companies are better positioned for that world than the market realizes. U.S.-centric manufacturers are gaining leverage. Vertical integration is back in vogue. Even some tech names are seeing margin benefit from accelerated AI adoption that lowers their reliance on human capital.

Europe re-armament: a fiscal impetus

In Europe, a significant development with potential macroeconomic implications is the move towards increased defence spending, particularly in Germany. The German government's decision to relax its debt rules to accommodate a substantial €1 trillion defence-spending package has raised eyebrows. While the intention behind this fiscal expansion is to stimulate the economy, its actual impact on growth is projected to be minimal, adding only 0.1%. This limited growth effect is attributed to the low economic multiplier associated with defence spending.

Moody's warns that Germany’s decision to relax its debt rules will lead to rising debt levels in the medium term, instead of the previously expected decline. While the extra spending is meant to boost the economy, its impact on growth will be minimal—only adding 0.1ppts. This is because much of the money is going toward defense, which has a low economic multiplier effect.

This increased defence spending has also contributed to a rise in German real interest rates. The 10-year real interest rates have climbed to 0.92%, the highest level since 2011, and the Bund got close to the psychological 3% level. This increase is driven by investors demanding a higher real return due to Germany's perceived weaker creditworthiness, as long-term inflation expectations have remained largely unchanged. The implications of this fiscal expansion and the resulting increase in borrowing costs for Germany, and potentially for other European economies, remain a key area of focus for market participants.

Fed March FOMC: dovish pause

The Federal Reserve's stance, as articulated in the March FOMC meeting, reflects a dovish pause with clear communication of stagflationary risks stemming from tariffs. The Fed has maintained its wait-and-see approach, holding the benchmark federal funds rate steady at 4.25%-4.5%. While anticipating two rate cuts totalling 50 basis points by the end of 2025, the Fed has revised its economic outlook, lowering the 2025 GDP growth forecast to 1.7% (from 2.1%) and raising the unemployment rate forecast to 4.4% (from 4.3%). Inflation projections have also been adjusted upwards, with PCE inflation for 2025 now at 2.7% (from 2.5%) and core PCE inflation at 2.8% (from 2.5%) by year-end.

In a notable move, the Fed announced a slowing of its balance sheet runoff (QT), reducing the monthly Treasury redemption cap to US$5 billion (from US$25 billion), while the MBS cap remained at US$35 billion. This decision, however, was not unanimous, with Fed Governor Waller dissenting on the QT reduction.

Fed Chair Powell has acknowledged the increased uncertainty in the economic outlook, stating that the base case is for the inflationary impact of tariffs to be “transitory.” He has also emphasized that the Fed is not in a hurry to move on rate cuts, preferring to await further clarity given the elevated uncertainty. Powell has highlighted the uncertainty stemming from President Trump's tariffs, noting a disconnect between hard data and surveys.

Looking ahead, several factors are expected to influence the trajectory of interest rates. Credit Agricole forecasts that Treasury yields could decline modestly in Q2 2025, reflecting the negative impact of tariffs on growth and the Fed resuming rate cuts in June and September. However, rates could potentially rise in the second half of 2025 if President Trump's pro-growth policies, such as tax cuts and deregulation, come into effect. Their 10-year 2026 year-end target is now 4.75%, revised down from 4.95% in the prior forecast, reflecting a less optimistic growth outlook.

Deutsche Bank suggests that a U.S. recession is possible even without a significant decline in 10-year Treasury yields. While typical U.S. recessions are triggered by negative demand shocks, usually resulting from tight monetary policy, the current situation presents a different dynamic.

There is limited evidence of material fiscal tightening, but there are indications that trade policy could trigger a negative supply shock, leading to both higher inflation and a higher unemployment rate. This scenario, unlike a traditional negative demand shock, might not result in lower 10-year yields, as the Fed may be constrained from easing policy due to rising inflation expectations.

Options traders are dialling back expectations for Fed rate cuts. One new position this week, with a premium of more than US$ 10m, would benefit if the Fed avoids making any moves this year, and do even better if the next change is a rate hike.

In the Treasury market, the five-year sector is gaining prominence as a preferred trade amidst tariff uncertainties and concerns about U.S. growth. The options market reflects this preference, with increased demand for exposure to five-year notes. This sector is seen as offering a balance of safety, being less sensitive to Fed policy compared to two-year notes and less vulnerable to economic health and deficit concerns compared to 10-year and 30-year notes.

Credit and Interest Rates: choppy waters

The credit markets have exhibited a sense of calm till few days ago, but more recently spreads have started to widen indicating increased worries about the U.S. recession risks, starting to resemble equity and rate markets behaviour.

We have experienced a notable divergence in credit markets: European credit spreads have shown only a mild correction, while U.S. spreads widened significantly. Two key factors appear to be driving this transatlantic imbalance: 1) heightened economic concerns in the US – a rare transatlantic imbalance. 2) the Bund underperformance has helped anchor EUR spreads, unlike in the U.S. where Treasuries offered less support.

Over the past two and a half years, High Yield bonds have appeared attractive and offered a remarkably resilient behaviour. The main reason for this was the high risk premium (credit spread) since mid-2022. While these spreads are highly volatile, they tend to trade around their median value over the long term. Now, more than two and a half years after their peak in June 2022, risk premia for both USD High Yield and, more recently, Euro High Yield bonds have fallen to such low levels that, in our analysis, they appear simply too “expensive”. Historically, when risk premiums were more than one standard deviation below their median value, a significant increase in credit spreads followed within approximately 6 to 12 months – accompanied by negative performance in High Yield bonds. While the exact timing of these reversals varied, the pattern has been consistently observed. Currently, the valuation of this bond segment suggests a rather unattractive outlook. The strong performance of the past two and a half years could at least temporarily lose momentum.

As tariffs from the White House threaten to damage some companies’ balance sheets, leveraged finance investors are searching for debt tied to relatively stable companies that can absorb the potential impact from a trade war. They’re finding that in the high yield bond market, which has picked up former investment-grade names while losing some of its riskiest members to the nascent private credit sector. In fact, a popular trade right now is selling leveraged loans and buying better-rated junk bonds, said Benjamin Burton, the global head of leveraged finance syndicate at Barclays.

The high yield market is also benefiting from an influx of “fallen angels,” or companies that have been downgraded from investment-grade to junk. As of last month, the volume of corporate debt falling to high-yield from investment-grade was the highest since 2020, Goldman Sachs analysts wrote in a February note, adding that the downgrades reflect company-specific issues, rather than being a sign of a “macro shock.”